Before COVID-19, Annie Frodeman held two-part time jobs, one as a ramp agent for Piedmont Airlines in Burlington and another registering ER patients at the University of Vermont Medical Center.

She often worked more than 40 hours a week, but her hours dried up once the pandemic struck. First, she was furloughed by the airline; then she saw her hours at the hospital cut to a single shift.

“Last week I didn’t get anything,” she recently told The New York Times.

In Picking Up Work Here and There, Many Miss Out on Unemployment Check https://t.co/rXuos6La65

— Annie Frodeman (@AFrodeman) July 23, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has been hard on everyone—well, almost everyone—but it has perhaps been hardest on part-time workers. Unlike full-time workers, part-time workers often are not eligible to receive state unemployment benefits.

When they are eligible, they often have to navigate a regulatory labyrinth to find out if they are eligible and then begin receiving benefits.

“Most states have specific rules regarding part-time availability that add barriers to Unemployment Insurance eligibility,” says a report by the National Employment Law Project. “Limitations on overall work hours, times of day, or days of the week imposed by health, disabilities, caregiving responsibilities, or other factors can prevent claimants from receiving UI benefits in any state.”

Frodeman was one of an untold number of Americans who haven’t received an unemployment check. In May, she applied for federal benefits through the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance initiative—a program designed specifically for freelancers, part-timers, and gig workers who last work during the crisis—but so far has not had any luck.

The program has been plagued by abuse and fraud. Last week, Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan announced the state had uncovered a criminal enterprise involving 47,500 fraudulent unemployment claims totaling more than $500 million.

Fortunately, the Times reports, Frodeman is back to work part-time at the airline that furloughed her months before.

America’s ‘Involuntary’ Part-Time Workforce

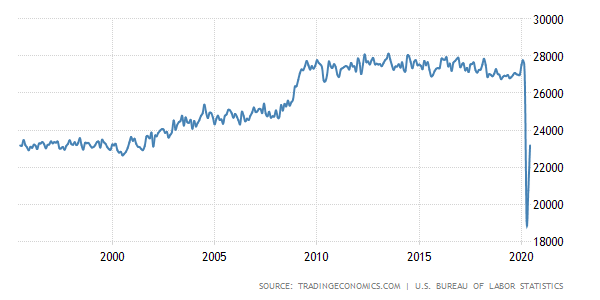

Prior to the pandemic, about 28 million Americans worked part-time jobs. For many of these individuals, working part-time is a preference.

As we’ve pointed out at FEE, part-time work and freelance gigs can have their perks: work-life balance, flexibility, new job experience, an opportunity to work toward a dream, and many other offerings. (One such person may be Frodeman, a part-time graduate student who told the Times she enjoyed the flexibility part-time work offered.)

It’s also true that many part-time workers desire a full-time job. Data show that millions of Americans are “involuntary” part-time workers, meaning they’d prefer to have full-time work.

Pre-COVID, there were between 6 and 7 million such workers in the US. According to the Economic Policy Institute, the percentage of involuntary part-time workers in the US in recent years has been considerably higher than it was prior to the Great Recession, about 45 percent greater.

In her article at the Times, Patricia Cohen writes that part-time workers often suffer from “absence of benefits like sick days and health insurance” and other job perks. This is true, but what she doesn’t mention is that government regulations and pressure from labor activists can result in distorted labor markets that leave many workers sidelined or underemployed.

Pricing Workers Out of Full-Time Jobs

Many people cheered last year when Target announced it was raising its pay floor to $13 an hour to appease the labor movement, calling it “wage justice.”

But the move was hardly helpful to experienced employees who saw their hours slashed to cover wage increases for less qualified workers and those with less work experience. Workers like Bonnie Furlong, who usually worked 32 to 38 hours a week, suddenly saw her timecard slashed to 20 hours per week.

“I’m basically making less than I was before they raised it to $13 an hour,” Furlong told The Guardian.

Furlong was just one of many Target employees who lost hours from the pay-floor and became part-time employees. For some workers, Target’s decision cost them their benefits and even their jobs.

Marie Biggs of Dallas, for example, had worked at Target for 14 years. But the new policy saw her hours reduced (and her workload increased) to the extent that she lost her benefits. So Biggs quit. Target lost an experienced employee; Biggs lost a job she valued.

“I planned on retiring from Target,” she said.

The goal here is not to pick on Target. The retailer was just one of scores of companies, cities, and states that adopted wage floor policies with the intention of helping workers by implementing “wage justice.”

The point is to demonstrate that these policies do not come without consequences that are often borne by the most vulnerable workers.

We know that many employers respond to minimum wage laws by reducing worker hours. Basic economic theory tells us why.

As economist John Phelan has shown, the simple model of supply and demand tells us that increasing labor prices leads to less labor demand. Employers, however, don’t have to layoff workers (though sometimes they do). A more subtle reaction is to simply reduce workers’ hours, which results in greater under-employment.

The Lesson of Interventionism

The minimum wage is of course just one way interventions result in a larger “involuntary” part-time workforce. Any government regulations that artificially increase the price of labor, such as mandates that employers provide insurance plans for employees, have a similar effect.

What’s particularly sinister is that when these regulations invariably fail to produce the desired results, they do not result in less regulation. In a kind of paradox, they tend to breed more interventionism, the economist Ludwig Von Mises observed.

“All varieties of interference with the market phenomena not only fail to achieve the ends aimed at by their authors and supporters but bring about a state of affairs which — from the point of view of their authors' and advocates' valuations — is less desirable than the previous state of affairs which they were designed to alter,” Mises wrote.” If one wants to correct their manifest unsuitableness and preposterousness by supplementing the first acts of intervention with more and more of such acts, one must go further and further until the market economy has been entirely destroyed and socialism has been substituted for it.”

If Mises is correct, policymakers will not look at the situation of Ms. Frodeman and countless other Americans and realize millions of workers would have been full-time employees if not for interventions that artificially increased the price of labor at their expense.

They will look at the situation and determine we need more regulations and interventions to “protect” workers from the next economic crisis.

If Americans wish to avoid the vicious cycle Mises describes, they must realize every intervention of the free market comes with costs that—like the butterfly that flaps its wings thousands of miles away—will reverberate beyond its own province.