What do some of the world’s biggest and most recognized corporations do with their money? Is it true that they are flushed with cash reserves? Do they sleep on top of their piles of rubies and gold like human dragons?

While that tweet is in reference to individuals, it still captures a misconception held by many. Do wealthy individuals and megalithic corporations hoard vast sums of cash, only to have their piles grow larger and larger over time? Some might believe this to be true.

However, the truth is that corporations are constantly investing dollars back into their business operations rather than simply sitting on their capital. Capturing market-share is a competitive process that requires constant reinvestment and innovation. Because of this, some of the largest corporations in the game turn profit margins lower than you would expect. Let’s take a look at what some of these corporations actually do with their money, it might surprise you.

Amazon

It’s no secret that Amazon is one of the biggest corporations in the game (#28 on the Forbes Global 2,000 list). Amazon reported a whopping $232.9 billion in revenue for 2018. However, in profit alone, they only took away $10.1 billion. That’s a profit margin of less than five percent.

Headway Capital, in the flowchart above and the summary below, details how the remaining $222 billion is spent:

Amazon...has strongly favored growth over profits, reinvesting much of its revenue in improvements to its last-mile delivery infrastructure, the expansion of its Prime membership base, and the development of new business ventures. The e-commerce giant did not turn a profit until Q4 2001, and has had several unprofitable quarters since.

Nike

One of the largest clothing brands and sponsor to the NFL, NBA, and hundreds of colleges and athletes, Nike ranks #280 on the Forbes Global 2,000 list and was the third-largest apparel company in the world in 2018, edging out Adidas but behind Christian Dior and Zara. Nike generated $36.4 billion in revenue but only took away $1.93 billion in profit. That’s a profit margin of around five percent.

So where did all the revenue go? Headway Capital reports,

One of Nike’s biggest expenses is the promotion and strengthening of its brand. In fiscal 2018, Nike spent $3.6 billion on “demand creation,” which consists of advertising and promotion costs, including endorsement contracts, television, digital, and print advertising. Nike is also spending more on its physical stores and distribution chain as it attempts to boost its direct-to-consumer retail offerings. Nike spent $7.9 billion on operating overhead in fiscal 2018, a 9.9% increase from the year prior. Some of the spending likely went to the construction of its new Nike Live store, an interactive, smartphone-driven hub for NikePlus members in Los Angeles opened in July 2018.

Uber

Although Uber didn’t make the Forbes Global 2,000, the largest ride-hailing service in the world is still worth analysis. The relatively new company actually operates at a loss. For quarter two in 2019, Uber lost $5.2 billion and had its slowest-ever revenue growth. In 2018, Uber reported $9.8 billion in revenue and just under $1 billion in profit. That’s a profit margin of about ten percent.

So how did Uber spend its money? Headway Capital reports,

The company incurs significant growth costs when it moves to a new city, shelling out on sign-up bonuses to recruit new drivers and ride discounts help build new customer bases. Uber also invests heavily in R&D, spending $457 million on self-driving cars and other advanced technology, as well as $1.0 billion in other research and development expenses. While some R&D-heavy ventures, such as Uber Freight, have shown promise in the form of growing revenues — captured in the “Other Bets” segment — investors may not have patience for Uber’s growth-over-profit strategy. Shares of Uber fell 7.6% on the day of its IPO on May 10, 2019, losing a collective $618 million in value — the largest dollar loss in U.S. IPO history going back to 1975.

Disney

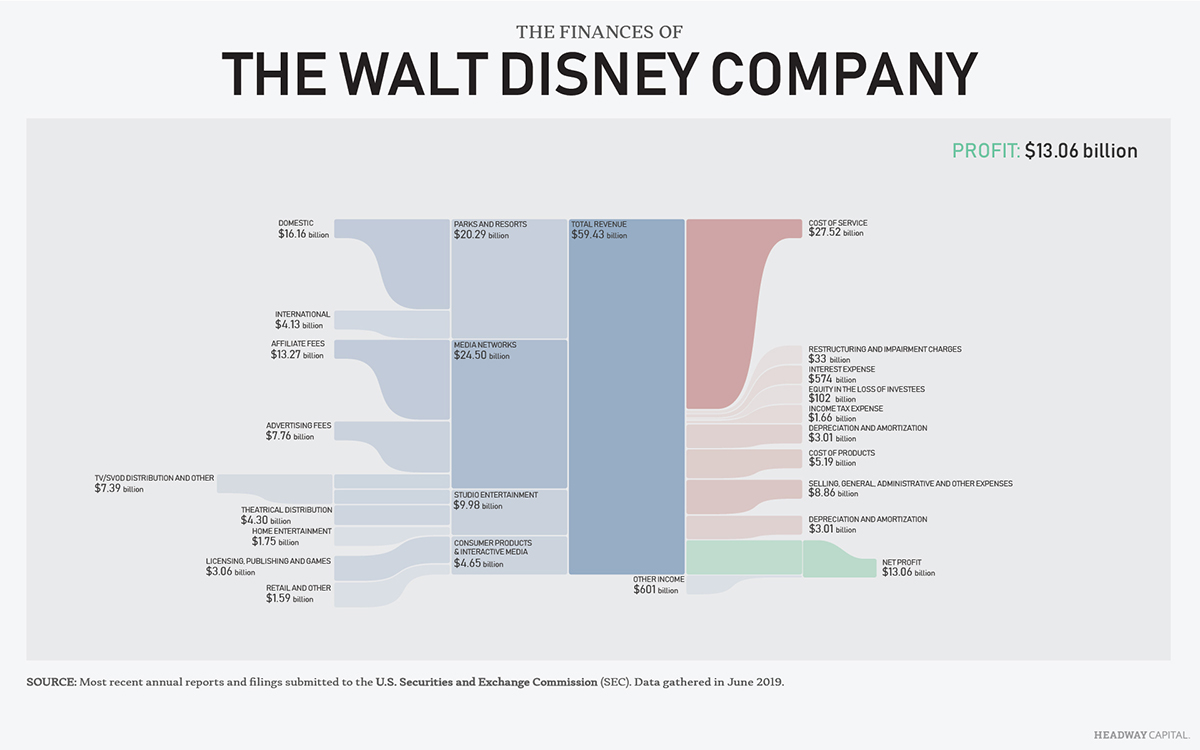

With worldwide notoriety, the world’s second-largest media company in 2019 and #70 on the Forbes Global 2,000 list for 2018, The Walt Disney Company, reported a stellar $59.43 billion in revenue generated and a substantial $13.06 billion in profit. That’s a profit margin of nearly 22 percent.

That’s a substantial profit. But where did the other $46 billion go? As Headway Capital reports, Disney is constantly pouring revenue into other media properties and new digital operations.

Disney has acquired a number of major media properties in the 21st century, purchasing Pixar in 2006, Marvel Entertainment in 2009, Lucasfilm in 2012, and, most recently, 21st Century Fox’s film and TV assets in March 2019. Disney is able to utilize new properties across its business segments, producing four Star Wars films since acquiring Lucasfilm and announcing four more through 2026, opening Star Wars-themed park lands at Disney World and Disneyland in 2019, and selling Star Wars merchandise throughout its Disney retail stores, for example. Other major properties majority-owned by The Walt Disney Company include ABC, ESPN, and Hulu.

The Upshot

In conclusion, an analysis of the previous companies, perhaps excluding Disney, reveals that some of the biggest corporations in the world run tight profit-margins compared to the revenue they generate, which might lay waste to the claim that they are easily taxable profit-generating megaliths.

The largest, most dominant companies in the world today are not necessarily the most profitable. In an attempt to establish a recurring revenue stream in the long term, some companies will sacrifice short-term profit and reinvest most of their income on customer acquisition and supply chain infrastructure. This tradeoff between growth and profit is often visually apparent in a company’s income alluvial.

Progressive politicians might want to factor this into their assessments of who is easily taxable, given they might someday understand the difference between profit and revenue.