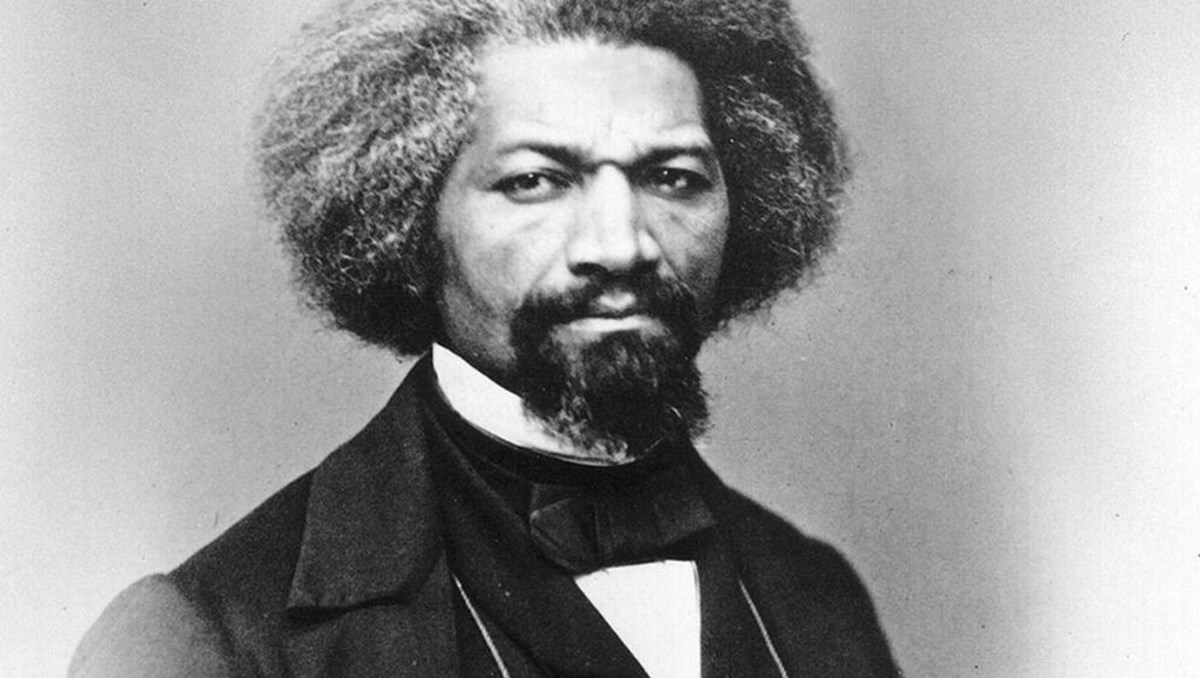

This is an excellent biography of a truly great American hero—the escaped slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Instead of telling your children about supposed heroes like George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and FDR, tell them instead about Frederick Douglass, and give them this book to read.

Timothy Sandefur—an attorney who is the author of several books and dozens of scholarly articles—has given us concise account of the life and ideas of Frederick Douglass in a mere 119 pages. The writing is excellent throughout, which makes Frederick Douglass: Self Made Man a pleasure to read.

A valuable aspect of this book (to libertarians at least) is Sandefur’s contention that individuality is the centerpiece of Douglass’s moral and political philosophy. He also criticizes those left-historians who have downplayed or ignored this feature. For example, Sandefur makes the following observation about Angela Davis’s comments in an edition of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass:

Her notes make no mention of Douglass’s hostility to communism, his skepticism of labor unions, his unequivocal opposition to black nationalism, or his allegiance to limited government and free enterprise. Other scholars have openly condemned Douglas for his “bourgeois” belief in “laissez-faire,” and his “blinkered” “faith in the miraculous workings of the free labor market,” and have even claimed he was “being manipulated by the ideology of “self-possessive individualism.”

Sandefur portrays Douglass as a classical liberal, but nowhere does he discuss Douglass’s strong support for the legal prohibition of alcoholic beverages. This, of course, was a common position among Garrison, Phillips, and other abolitionists, but it would have been interesting to see Sandefur’s explanation for this obvious inconsistency in the position of those abolitionists who were sympathetic to the classical liberal agenda in other respects.

Perhaps the answer lies in an article that Sandefur wrote for the website “In Defense of Liberty.” In a reply to the contention of Nicolas Buccola that it is a mistake to classify Douglass as classical liberal, or libertarian, Sandefur replied:

What’s distinctive about the libertarian or classical liberal tradition is its overriding emphasis on the rights of the individual, as opposed to the purported “rights” of society or the state. The classical liberal begins with the idea that the individual is fundamentally entitled to freedom—to live his or her life without coercion from others. People create governments to protect them against coercion, so that they can lead their lives as they choose—and the government is therefore their servant, not their master….

Of these three, Douglass fits most comfortably by far into the classical liberal or libertarian category. He believed quite clearly that the individual is the sole bearer of rights, and that the government exists to protect those rights.

Sandefur may believe that prohibition was not fundamental to Douglass’s belief system, but, as I argued in several previous essays, prohibition certainly was fundamental to those abolitionists who sprang from a whiggish background of moral reform. Douglass, an escaped slave, did not share this background, so another explanation is needed. I suspect that Douglass picked up his enthusiasm for prohibition from his early association with the Garrisonian faction of abolitionism, though this is just a guess.

"My natural elasticity was crushed; my intellect languished; the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died out; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me, and behold a man transformed to a brute."

In addition to providing an account of Douglass’s life and activities, Sandefur also provides a brief but insightful analysis of slavery itself. Many of his observations are drawn from the three autobiographical books written by Douglass. Consider Sandefur’s discussion of how the slave Douglass was treated when he was sent to be disciplined by cruel slave-breaker named Edward Covey. Douglass was whipped regularly for six months, regardless of his behavior. As Sandefur notes, “Since only total subjugation could make slave labor productive, masters sought to inculcate a sense of utter domination in their human property.”

Thus, he beat Douglass weekly, for infractions real or imagined. He forced Douglass to labor in the fields in all kinds of weather—rain, snow, hail—and sent him on errands he could not possibly perform—handling oxen, for instance, for which he had no training. When he inevitably failed, Covey punished him with the lash. He spied on Douglass, sneaked up on him, and ambushed him simply to drill into his mind the idea that the master might be watching at any time.

Douglass confessed that this treatment broke him psychologically.

My natural elasticity was crushed; my intellect languished; the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died out; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me, and behold a man transformed to a brute.

Things changed for Douglass after he fought back against Covey. One morning Covey again attacked Douglass without warning, but this time Douglass threw him to the ground and warded off his blows for two hours. Other slaves refused to come to Covey’s aid, and when Covey’s cousin attempted to help, Douglass punched him so hard that he stumbled and left the scene. Covey later claimed, falsely, that he had “whipped” Douglass. In any case, this was the last beating Douglass received from his sadistic overseer. Sandefur says of this incident:

[Douglass] has proven to himself that he retained something essential that could not be taken away. The experience “was a resurrection from the dark and pestiferous tomb of slavery, to the heaven of comparative freedom. I was no longer a servile coward….I had reached the point at which I was not afraid to die. This spirit made me a freedman in fact, though I still remained a slave in form.”

This moment became the centerpiece of Douglass’s own story. He told the tale time and again, to illustrate the basic theme of his life’s efforts. Those who desired freedom had to prove themselves worthy of it by struggle and self-determination. To be fully human meant to command oneself and to hazard life for the reward of living. In a sense, the fight with Covey hardened him—rendering him less likely to compromise and making him uncomfortable with the pacifism that animated the Quaker abolitionists. But it also gave him a sense of seriousness and integrity that was all his own. He might be ordered about, could be beaten or even murdered, but at 16 years old, his self once again belonged to him, and it would always remain that way. “Bruised did I get, but the instance I have described was the end of the brutification to which slavery has subjected me.

I wish to conclude this review with a few comments about Douglass’s attitude toward Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. Like all abolitionists, Douglass understood that Lincoln waged war not to liberate slaves but to save the Union. Douglass was therefore quite critical of Lincoln during the early stage of the war. In 1852, Douglass said that “the most painful and mortifying feature present in the prosecution and management of the present war [was] the vacillation, doubt, uncertainty and hesitation which have thus far distinguished our government in regard to the true method of dealing with [slavery].”

Frederick Douglass was a remarkable man, and Sandefur does him justice.

After Douglass met with Lincoln personally, he changed his attitude somewhat, believing that Lincoln was reluctant to declare abolition a purpose of the war, because this would alienate the many racist northerners who would not fight to liberate slaves. And Douglass was encouraged by the Emancipation Proclamation (January 1, 1863), which freed slaves only in the rebellious states as a “war measure.” This was at least a step in the right direction. But even a decade after Lincoln’s assassination, Douglass said that Lincoln was “preeminently the white man’s president.” Lincoln based his political calculations on the potential benefits to the white man, not the black man.

I have not discussed Sandefur’s treatment of many issues, but I hope I have provided enough information to convince readers to read Frederick Douglass: Self Made Man. Frederick Douglass was a remarkable man, and Sandefur does him justice.

This Libertarianism.org article was republished with permission.